Voodoo

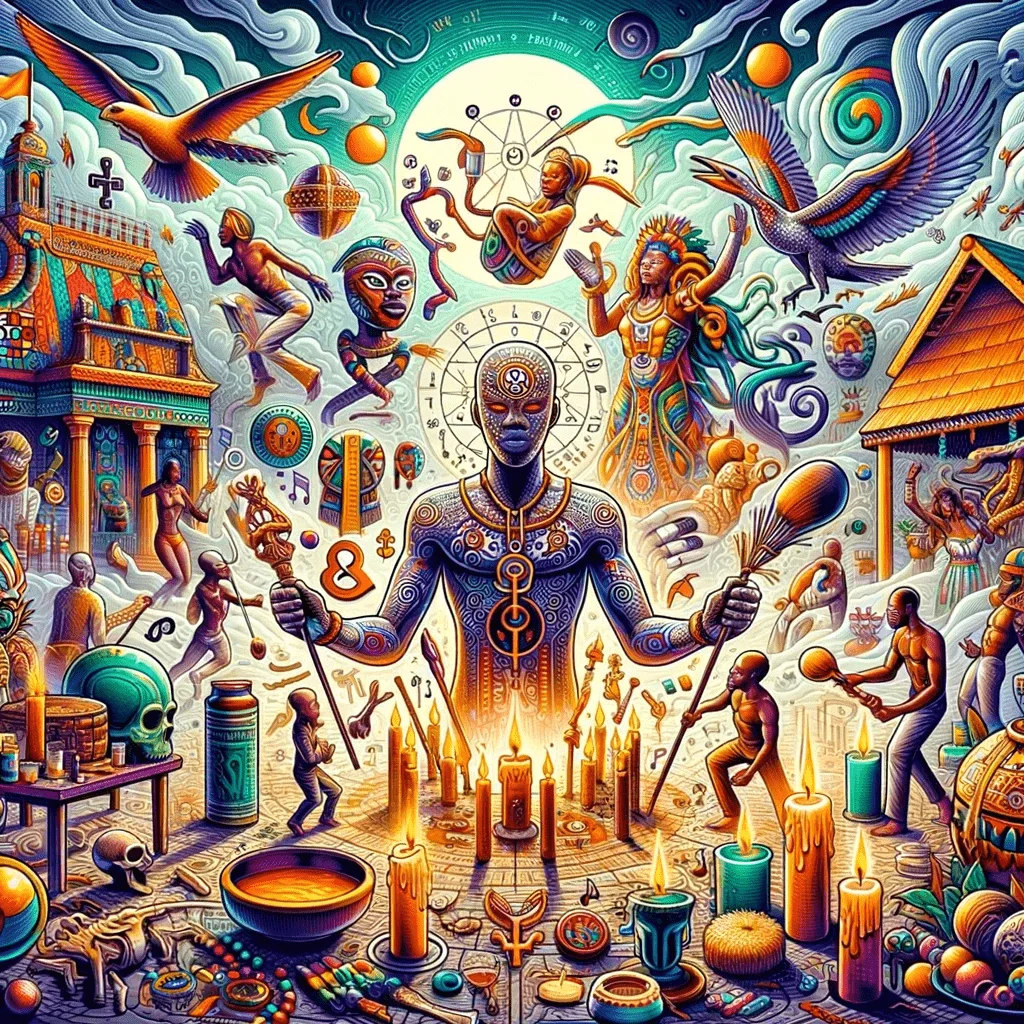

Voodoo, also known as Vodou or Vodun, is a complex spiritual tradition deeply rooted in the cultural fabric of West Africa, the Caribbean, and the southern United States, particularly in Louisiana. Its origins trace back to the Dahomey Kingdom in present-day Benin, dating as far back as the 18th century when the Atlantic slave trade forced the transplantation of these beliefs to the Americas.

Voodoo is not an abstract or superstitious practice but a tangible religious system with specific rituals, symbols, and deities. The religious structure revolves around the veneration of ancestral spirits known as ‘loa’ or ‘lwa,’ each of which is associated with specific elements, characteristics, or human concerns. These spirits serve as intermediaries between the material world and the supreme deity, Bondye, who is considered too distant to engage directly in human affairs.

The loa, also spelled as lwa, are fundamental to the practice of Voodoo, especially in the Haitian tradition. They are spiritual beings or deities who act as intermediaries between humans and the supreme deity, Bondye, who is considered too distant to interact directly with human affairs.

The loa have distinct personalities, preferences, and domains of influence. For instance, some loa are associated with love, others with health, others with justice, and so forth. They can be invoked for help in their specific areas of influence. Also, each loa has its own symbols, colors, days, foods, and other elements associated with them.

Each loa is served in particular ways and with specific rituals, and practitioners form personal relationships with them through the act of service and reverence. It is believed that during certain ceremonies, the loa can possess the bodies of the practitioners, speaking and acting through them. This is known as being “ridden” by a loa.

Some well-known loa include:

- Papa Legba: He is the gatekeeper of the spirit world, controlling access to the other loa. He is typically the first loa invoked in a ceremony, to open the way to communication with the spirit world.

- Erzulie Freda: She is the loa of love, beauty, and wealth, often associated with femininity and passion.

- Baron Samedi: He is the loa of death and resurrection, known for his raucous personality. He presides over the transition of souls and is often depicted wearing a top hat and a skull face.

It’s important to note that the loa are not considered ‘gods’ in the Western sense. Rather, they are spiritual entities with their own agency, who can be petitioned for aid or guidance. Relationships with the loa are reciprocal, with practitioners offering service, reverence, and offerings, and the loa in turn offering guidance, protection, or assistance.

Voodoo practitioners believe that the spirits can be appeased or communicated with through various rituals, including music, dance, animal sacrifices, and the creation of elaborate ‘veve’ symbols using cornmeal or other powders. In this sense, Voodoo is a religion steeped in oral tradition, material culture, and communal participation. Practitioners also believe that the loa can possess individuals during these rituals, providing guidance or prophecy.

Voodoo’s science is not as literal as in modern physics or biology. Instead, it is a spiritual science, dealing with the unseen connections between humans, the spiritual world, and the natural world. Voodoo’s practitioners, for instance, use herbal medicines and spiritual baths in their healing rituals. This intertwining of physical and spiritual healing is a part of what is sometimes referred to as ethnomedicine.

Many experts like Karen McCarthy Brown, author of “Mama Lola: A Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn,” have explored Voodoo as a complex system of healing and community-building. They note that the religion has historically been stigmatized and misunderstood due to racial and cultural prejudice, which has also influenced how it is portrayed in popular culture and media.

Publications such as The New York Times have reported on Voodoo’s role in communities, particularly in times of crisis. For instance, in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, articles highlighted the importance of Voodoo ceremonies in providing comfort and promoting unity among affected communities.

In authentic Voodoo practice, dolls can sometimes be used, but not for the purpose of inflicting pain or harm. Rather, they serve as a symbolic representation of a particular spirit or a particular person, often used in healing or protection rituals. The idea of sticking pins into a doll to cause harm to another person is largely a product of Hollywood and does not accurately represent the beliefs or practices of Voodoo.

It’s also worth noting that similar symbolic objects are used in many cultures around the world. For instance, ‘poppets’ were used in European folk magic traditions, and ‘effigies’ have been used in various indigenous cultures. In all of these cases, the intent is typically positive or protective, rather than harmful.

- Voodoo’s influence on music: As noted by Dr. Kyrah Malika Daniels in “Race, Religion & Black Lives Matter: Essays on a Moment and a Movement,” the rhythms and chants in Voodoo rituals have influenced numerous forms of music, including blues, jazz, and rock ‘n’ roll.

- Syncretism in Voodoo: According to “Creole Religions of the Caribbean” by Margarite Fernández Olmos and Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert, Voodoo often blends with Catholicism, especially in Haiti and Louisiana. This practice known as syncretism allows enslaved Africans to continue their spiritual traditions under the guise of Catholic saints.

- Voodoo’s respect for nature: In “Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti,” filmmaker and author Maya Deren highlights that Voodoo has a deep respect for the environment, seeing it as infused with spiritual presence. This respect is expressed through various rituals and taboos designed to maintain balance with the natural world.

Voodoo is underpinned by a deep history and a profound connection to community, ancestry, and nature. Far from being a fringe or ‘dark’ religion, it provides a holistic worldview that harmonizes the material and spiritual realms, and it is a vital source of identity and solidarity for its practitioners.

The traditions, rituals, and beliefs of Voodoo vary widely, reflecting the diverse cultures and histories of the regions where it is practiced. From the communal drumming and chanting rituals of Haitian Vodou to the colorful Mardi Gras Indian parade traditions influenced by Louisiana Voodoo, the practice is as varied as it is vibrant. Yet, these various forms of Voodoo share a common respect for the potency of the unseen world, the significance of ancestry, and the interplay between humans and spiritual entities.

Modern interpretations of Voodoo continue to evolve, incorporating elements of contemporary religious thought, social justice movements, and alternative healing practices. At the same time, practitioners are challenging negative stereotypes and working to preserve the religion’s traditions in the face of globalization and cultural change.

There are numerous books that provide valuable insights into the beliefs, practices, and history of Voodoo. Here are a few of them:

- “Mama Lola: A Vodou Priestess in Brooklyn” by Karen McCarthy Brown: This is an ethnographic study of a Haitian Vodou priestess living in Brooklyn. It provides an intimate look into the daily life and practice of Vodou.

- “The Serpent and the Rainbow” by Wade Davis: This book explores the biochemical basis of the Vodou practice of creating “zombies”. While it does not cover the entirety of Vodou practice, it provides a scientific exploration of one of its most misunderstood aspects.

- “Voodoo in New Orleans” by Robert Tallant: This book provides a comprehensive history of Voodoo as it developed in New Orleans, one of the major centers of the religion in the United States.

- “The Vodou Quantum Leap” by Reginald Crosley: Crosley, a medical doctor and a practitioner, discusses Vodou from the perspectives of quantum physics and alternative spirituality.

- “Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti” by Maya Deren: This book explores the rituals and deities of Haitian Vodou. It’s especially noteworthy for its discussion of the “loa”, the spirits venerated in Vodou practice.

- “Creole Religions of the Caribbean” by Margarite Fernández Olmos and Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert: This book covers several African diaspora religions, including Vodou, providing a broader context for understanding Vodou as part of a larger religious tradition.

In a world often driven by technological progress and material concerns, the spiritual insight and community focus of Voodoo offer a reminder of the value of connection, tradition, and the unseen world in human life.