The Word of God

The word “Bible” does not actually appear in the Bible itself. Instead, the collection of sacred texts refers to itself using terms like “Scripture,” “the Law,” “the Word of God,” and “the Prophets.” Among these, “the Law” is most common, followed by “the Word of God” and “the Scriptures,” which is how both Jesus and the apostles referred to earlier writings. The term “Bible” comes from the Greek word biblia, meaning “books,” and was later adopted by early Christians to describe the entire canon of sacred texts. This evolution of language reflects how the Bible came to be recognized as a unified, authoritative volume rather than a scattered group of scrolls.

But over time, the Word of God has been preserved not just as written law, but as a living force—spoken into existence. What if this force operates beyond language itself… guiding us across the threshold between physical and spiritual realms?

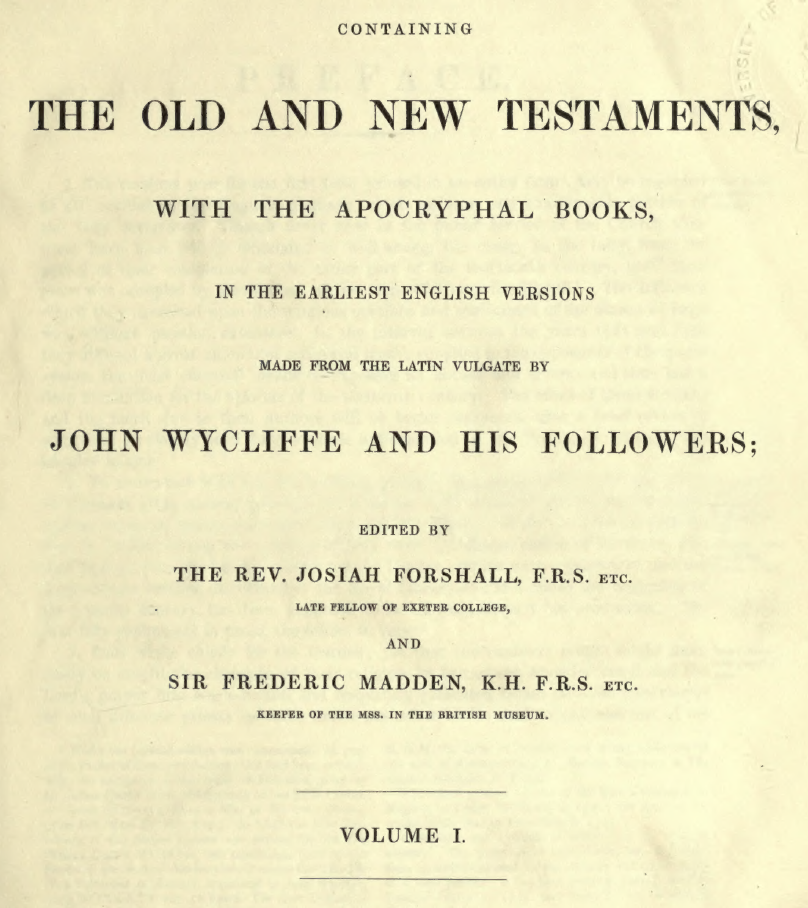

The Wycliffe Bible (c. 1382–1395) stands as the first complete English translation of the Bible, created by John Wycliffe and his followers more than a century before the printing press reached England. Translated from the Latin Vulgate into Middle English and painstakingly hand-copied, it made Scripture accessible to everyday people—something the Church viewed as threatening. At that time, the Church relied almost exclusively on the Latin Vulgate, a version only clergy and scholars could read. Wycliffe’s outspoken views on ecclesiastical corruption and papal overreach alarmed Church leaders. Though he died of natural causes in 1384, his teachings were later condemned at the Council of Constance in 1415. In a symbolic act of rejection, Church authorities ordered his bones exhumed, burned, and scattered in the River Swift. Despite the opposition, Wycliffe’s work laid the groundwork for future English Bibles and the principle that Scripture should be available to all.

William Tyndale’s New Testament (1526) was the first printed English Bible translated directly from the original Greek, making it a transformative milestone. Tyndale’s mission was to give the English people a Bible they could read and understand—a goal that made him a target. He fled England, working in secret across Europe, but was eventually betrayed, imprisoned, and executed in 1536. Still, his translation was so precise, clear, and lyrical that more than 80% of the King James Version’s New Testament would later echo his phrasing. Tyndale’s words brought the early Christian message closer to the people than ever before—and he paid with his life for that vision.

Created by English Protestant exiles in Geneva during Queen Mary’s persecution, the Geneva Bible (1560) built directly on Tyndale’s foundation. It introduced modern features such as verse numbers, marginal notes, and a readable, study-friendly layout. The Geneva Bible became immensely popular and influential—it was the version used by Shakespeare, the Puritans, and the Pilgrims who carried it to the New World. Its notes were often critical of monarchs, which led to its eventual suppression by those in power. Still, for the common reader, the Geneva Bible represented not just access to Scripture, but a deeper, more personal engagement with faith and freedom.

Commissioned by King James I to resolve religious division and replace politically charged translations, the King James Version (1611) was created by a team of 47 scholars who drew upon Tyndale’s earlier work along with Hebrew and Greek manuscripts. The result was a literary masterpiece, praised for its rhythmic beauty, doctrinal balance, and spiritual gravitas. While it omitted the controversial footnotes of the Geneva Bible, its soaring language and unifying intent helped it become the most enduring English Bible ever printed. The King James Version didn’t just shape theology—it shaped English literature, culture, and identity.

Beyond the historical battles for translation and access, the Bible continues to provoke deeper questions—not just about faith, but about the origins of humanity itself. Some researchers point out that the creation story in Genesis, with its plural language (“Let us make man in our image”), hints at something more complex than a singular divine voice. Could these ancient texts be preserving veiled references to otherworldly beings, misunderstood in their time but seen today through a new lens? Whether divine council, angelic host, or something less terrestrial, the Genesis narrative still stirs speculation about our true beginnings—and what else may have been guiding us all along.

And it doesn’t stop with creation. The account of the Great Flood in Genesis also takes on a strange new light when viewed through this expanded lens. Some interpretations suggest the flood wasn’t just divine judgment—it was a reset. Ancient texts like the Book of Enoch describe the Nephilim, hybrid beings born of “the sons of God” and human women, who corrupted the earth. This cross-species interference sounds eerily like modern tales of genetic manipulation by non-human intelligences. Could the flood have been an attempt to wipe clean a contamination—biological or spiritual—that spiraled out of control? When you strip away the layers of symbolic language, you start to see something more targeted, almost surgical, in the way these ancient events unfolded.

The Bible is replete with accounts of angelic interventions that further blur the lines between the divine and the otherworldly. From the fiery sword-wielding Cherubim guarding Eden to the radiant beings announcing pivotal events, these narratives suggest a consistent presence of celestial entities interacting with humanity. Such accounts invite contemplation: are these descriptions of divine messengers, or could they be ancient interpretations of encounters with non-human intelligences? The recurring theme of beings descending from the heavens, delivering messages, and influencing human affairs resonates with modern accounts of extraterrestrial encounters, prompting a reevaluation of these ancient texts in light of contemporary perspectives.

The distinction between fallen angels and demons adds another layer to this narrative. Fallen angels, once celestial beings, are often portrayed as possessing significant power and the ability to transform into various forms, including objects like spacecraft or other entities. Their capacity to maintain chosen forms for extended periods suggests a sophisticated means of disguise and influence. Demons, on the other hand, are depicted as having more limited transformational abilities, often maintaining a specific form and dissipating more quickly than fallen angels.

With so much sacrifice, brilliance, and courage poured into making the Scriptures available in English—and with multiple historical versions now freely accessible to anyone with an internet connection—there is no reason why we should not all be reading it. These texts have endured fire, censorship, exile, and death, and yet they remain. The words of life have been preserved—not hidden—and it is becoming increasingly clear that this is not just any book. It is, as it has always called itself: the Word of God.

But perhaps the most profound message of all is this: the Bible consistently emphasizes that what truly matters to God is not ritual or ceremony, but how we live and treat others. James 1:27 defines true religion as caring for orphans and widows in their distress and keeping oneself unstained by the world. Micah 6:8 reminds us to act justly, love mercy, and walk humbly with God. Jesus Himself criticized religious leaders for obsessing over ceremonial laws while neglecting justice, mercy, and faithfulness (Matthew 23:23). These scriptures highlight that genuine faith is demonstrated through compassion, justice, and service—not through empty rituals or appearances.

In a world where religious systems can sometimes overshadow the core teachings of love, mercy, and humility, it becomes vital to return to the living essence of the Scriptures. The enduring message is clear: live a life marked by real faith—demonstrated not in ritual, but in compassion, courage, and conviction.

Perhaps the Word of God isn’t just a set of sacred writings to study, but a divine current that speaks across dimensions—calling us to awaken, act, and align with something greater than words alone can contain.