Sacred Patterns are Divine Sounds

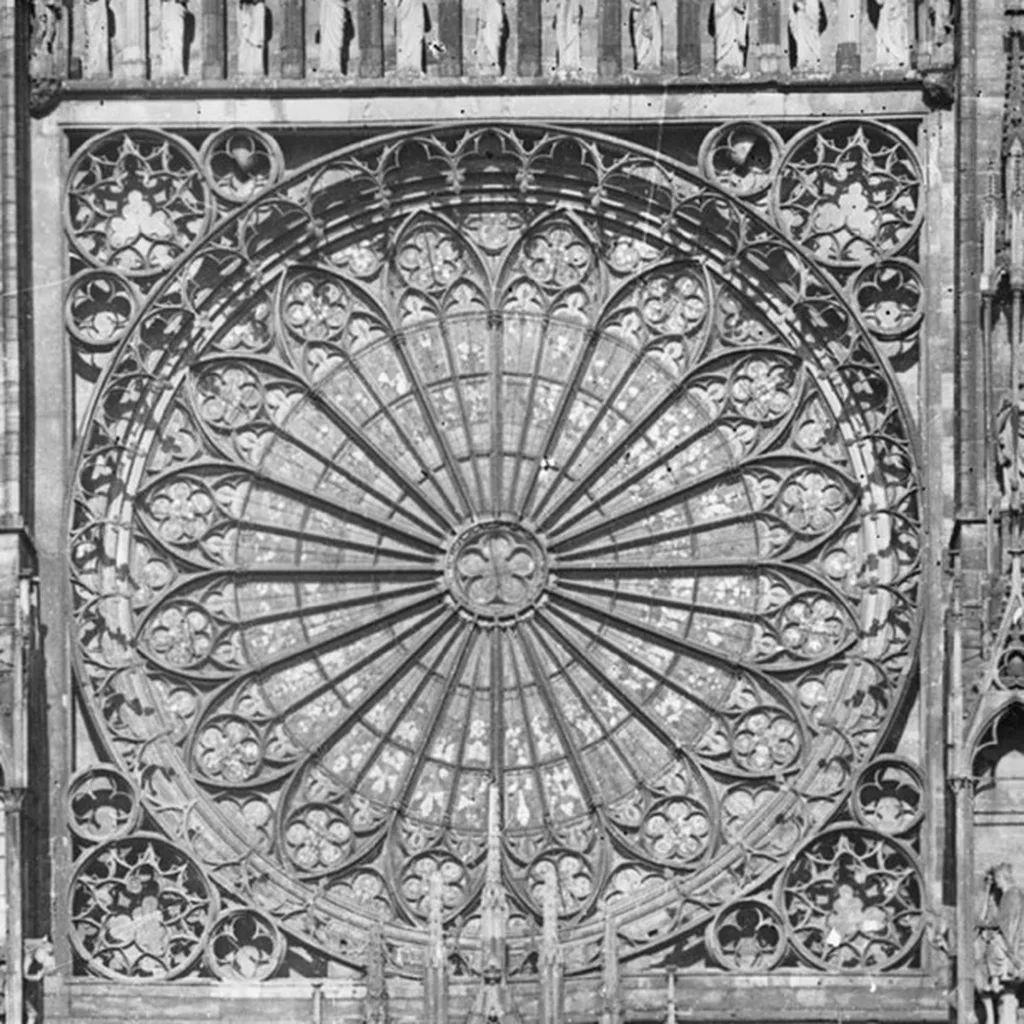

Throughout history, Gothic cathedrals have served as vessels of divine inspiration, embodying sacred geometry and harmonious proportions. Among their most awe-inspiring features are rose windows, intricate radial designs that symbolize celestial order and spiritual transcendence. In this study, we have taken the pattern of a Gothic rose window and transformed it into a sonification—a divine resonance that translates visual symmetry into an auditory experience. Sonification is the use of non-speech audio to convey information, typically translating visual or numerical data into sound. Rose windows are circular stained-glass compositions radiating from a central focal point, often found in the façades of cathedrals. Their structure is deeply mathematical, incorporating radial symmetry that mirrors the cycles of nature and celestial movements, harmonic proportions that reflect the same numerical relationships found in sacred music, and intricate tracery that adds layers of depth evoking a multi-dimensional spiritual experience. By extracting these elements and mapping them to sound, we sought to uncover the hidden music within their design. But one question arises: how could artisans in the late 1100s and 1500s know what healing sound frequencies look like?

This particular Gothic rose window is a masterpiece of medieval craftsmanship, designed by master stonemasons and artisans who sought to inspire awe and devotion. It is an elaborate stained-glass composition framed by intricate tracery, radiating from a central motif that symbolizes divine perfection and cosmic harmony. This architectural marvel is most commonly found in European Gothic cathedrals, such as those in France, where such designs flourished. The origins of these windows date back to between the late 1100s and the 1500s, a period during which Gothic architecture reached its zenith. Their purpose extended beyond aesthetic beauty, as they were designed to flood sacred spaces with colorful light, creating a spiritual experience for worshippers and reinforcing the idea of divine presence within the church. If these designs visually encode sacred harmonics that modern technology now allows us to translate into sound, were these builders consciously embedding healing frequencies into their work, or did they inherit a knowledge far older than the Gothic era itself? Some suggest that 352 Hz corresponds to the heart chakra, one of the primary energy centers in the body, believed to govern love, compassion, and emotional balance.

To convert this visual masterpiece into sound, we used a structured approach that aligned with its divine geometry. We began by analyzing the radial pattern of the window, measuring the distance from the center to define a frequency range. The brightness and contrast of different sections were then used to create varying intensities of sound. The outermost details corresponded to higher frequencies, producing ethereal tones, while the central structure anchored lower, foundational tones. The tracery patterns influenced modulation, introducing harmonic oscillations that mimicked the shifting light through stained glass. A stereo effect was implemented, with left and right channels dynamically shifting to reflect the window’s mirrored symmetry. Gradual oscillations were embedded to simulate the reverberation of sound within a cathedral’s vast acoustics, while a rhythmic pulse was added based on geometric segmentation, invoking the sensation of a living, breathing spiritual entity. After generating the sonification, we conducted an in-depth frequency analysis to confirm its alignment with the image’s structure.

The most prominent frequency in the final audio is 352 Hz, a note associated with sacred music and often linked to harmony and healing. The spectrogram analysis revealed recurring harmonic waves, reflecting the radial symmetry of the rose window. Fourier Transform analysis further confirmed that the frequency spectrum exhibits structured harmonic overtones, closely matching the layered tracery of the window design. These findings validate that the sound is not random noise but a structured, harmonic representation of the architectural form.

Interestingly, research into Solfeggio frequencies suggests that certain tones, such as 396 Hz, 432 Hz, and 528 Hz, have unique spiritual and physiological effects. These frequencies, associated with ancient Gregorian chants, are believed to influence consciousness and promote healing. The inclusion of 352 Hz within this framework raises questions about whether Gothic architects were unconsciously tuning their designs to specific harmonic principles that resonate with the human energy system. If Solfeggio frequencies can induce changes in human perception and well-being, is it possible that medieval builders embedded similar frequencies into their sacred spaces, long before modern acoustics confirmed their impact?

The resonance of 352 Hz, in particular, carries historical and spiritual significance, often appearing in ancient tuning systems associated with divine frequencies. There is also a growing discussion that lost knowledge from advanced civilizations may have played a role in these harmonic structures. Some theories propose that Gothic architecture, like other highly sophisticated ancient structures, aligns with principles that could have been inherited from an earlier, forgotten era. The Great Reset Theory and Mud Flood Events suggest that entire civilizations may have been buried or erased, leaving behind remnants of advanced technology hidden in plain sight. If the architectural precision of Gothic cathedrals encodes sacred acoustics, it raises the question of whether these builders were preserving a lost science that predates recorded history. Could the deliberate design of rose windows be a surviving link to an older, more advanced knowledge system of sound and energy manipulation?

How could medieval builders, working without modern sound analysis tools, have aligned their architectural proportions with frequencies now linked to spiritual well-being? Could this be evidence of an encoded sacred science, preserved through stone and glass for future generations to rediscover?

It was not until much later that scientists were able to visually see sound. In 1857, Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville invented the phonautograph, which transcribed sound waves onto paper, making their patterns visible. In 1885, Megan Watts Hughes demonstrated how sound could produce geometric patterns with the eidophone, and by 1908, Dayton Miller’s phonodeik advanced the ability to analyze sound visually. These developments raise the question—how did medieval builders seemingly embed harmonic structures that modern science is only now beginning to understand?

The final audio composition is more than just a mechanical translation—it is a living sonic representation of sacred architecture. Each harmonic structure mirrors the visual elegance of the rose window, and the resonant frequencies evoke the profound stillness of a sacred space. By listening to this sound, one can experience the beauty of a Gothic cathedral not only through sight but through the deeply immersive power of sound, revealing an underlying truth: geometry and music are two expressions of the same divine order. The question remains—was this knowledge a product of intuition, divine inspiration, or an ancient wisdom long forgotten?