Project Northern Tier

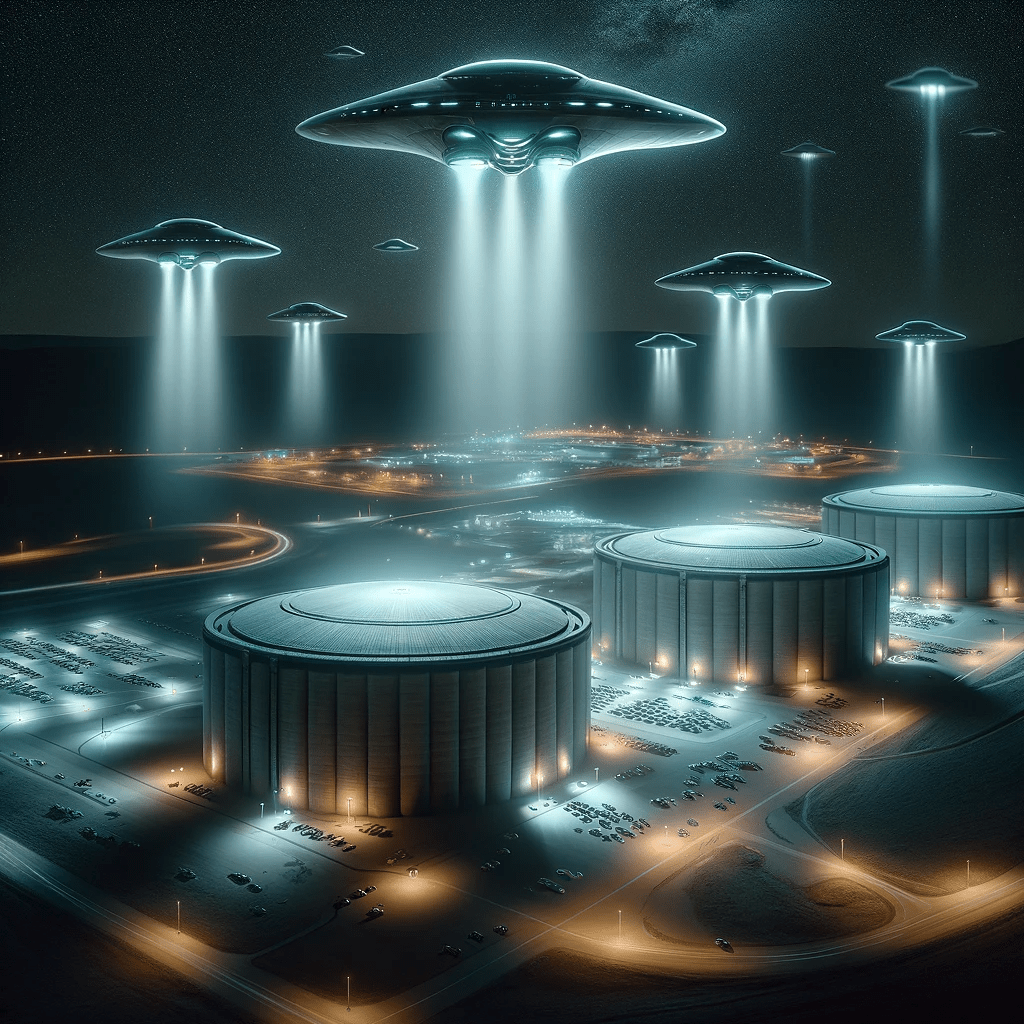

Project Northern Tier meticulously gathered comprehensive data and detailed records concerning numerous incidents where unidentified advanced aerospace vehicles breached airspace over secure Air Force bases housing nuclear arsenals. These intrusions occurred mainly during the 1960s and 1970s, and included incidents where these unidentified vehicles hovered over weapon storage areas and disrupted the operational capabilities of Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) systems. Such occurrences raise significant questions about national security risks to the United States.

Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) are long-range missiles capable of delivering a nuclear warhead over thousands of miles. These missiles are designed for strategic nuclear deterrence and are a critical component of a country’s national defense infrastructure. ICBMs can travel across continents, usually over a minimum range of about 3,400 miles (5,500 km), though some have much greater ranges.

While the specifics can vary widely, ICBMs are generally categorized based on their launch platforms, number of stages, and guidance systems. Here are some general categories:

- Silo-Based ICBMs: Stored in underground silos, these are the most common type and are ready to launch on command.

- Mobile ICBMs: Transported on heavy trucks or trains, these systems are harder to detect and can be relocated to avoid a first-strike attack.

- Submarine-Launched ICBMs (SLBMs): Launched from submarines, these offer the greatest degree of stealth and are extremely difficult to intercept.

- Multiple Independently Targetable Re-entry Vehicles (MIRVs): These are advanced ICBMs that can carry multiple warheads and direct them to different targets independently.

- Single Warhead ICBMs: Unlike MIRVs, these carry only one warhead per missile.

Several countries have developed ICBM technology:

- United States: The U.S. arsenal includes Minuteman III and the Trident II D5 SLBMs among others.

- Russia: Possesses a range of ICBMs including the Sarmat, Topol-M, and the Bulava SLBMs.

- China: The Dongfeng series is China’s primary ICBM arsenal, including the DF-41 which can carry MIRV warheads.

- France: The M51 SLBM is France’s main ICBM, typically launched from submarines.

- United Kingdom: Relies mainly on the Trident II D5 SLBMs, similar to the U.S.

- North Korea: Though less advanced, North Korea has been developing its own ICBMs, such as the Hwasong-15.

- India: While not officially confirmed, India is suspected of having ICBM capabilities with its Agni-V missile.

These countries invest heavily in the ongoing research, development, and modernization of ICBMs to ensure that they remain reliable and secure, given their role as a strategic deterrent. The use of these weapons has profound implications, and their existence raises important ethical and geopolitical questions, including concerns about proliferation and the risk of accidental launch.

Starting in the 1960s, various Air Force bases located in the northern regions of the United States, often referred to as the “Northern Tier,” reported multiple credible sightings. These observations were made by trained Air Force Base personnel and experienced pilots. These unidentified aerospace vehicles not only invaded restricted airspace but also displayed alarming behavior such as hovering over areas containing nuclear weapons and compromising the reliability of ICBM systems.

Specific bases that reported such activity include Malmstrom AFB in Montana, Loring AFB in Maine, Wurtsmith AFB in Michigan, Minot AFB in North Dakota, and Kirtland AFB in New Mexico. These incidents collectively serve as a potential indication of threats to the United States’ national security infrastructure.

Malmstrom AFB in Montana

- Size: Covers around 3,840 acres.

- ICBMs: Home to the 341st Missile Wing, Malmstrom AFB oversees Minuteman III ICBMs. The base is responsible for 150 Minuteman III ICBM silos scattered across Montana.

- Role: Primarily focused on nuclear deterrence, but also involved in other missions.

Loring AFB in Maine

- Size: The base, which was one of the largest in the U.S. Air Force, covered about 14,300 acres before its closure.

- ICBMs: Loring AFB did not host ICBMs but was a Strategic Air Command base focused on refueling and bomber missions.

- Role: Closed in 1994, Loring AFB was primarily a refueling and bomber base, part of the U.S. Strategic Air Command. It did not host ICBMs.

Wurtsmith AFB in Michigan

- Size: Covered an area of around 5,200 acres before its closure.

- ICBMs: Like Loring, Wurtsmith did not host ICBMs. It was primarily a bomber and aerial refueling base.

- Role: Closed in 1993, Wurtsmith was also a part of the Strategic Air Command but did not have ICBMs.

Minot AFB in North Dakota

- Size: Spans around 5,600 acres.

- ICBMs: Home to the 91st Missile Wing, Minot AFB oversees 150 Minuteman III ICBMs.

- Role: Dual mission base with both nuclear-capable bombers (B-52 Stratofortresses) and ICBMs, making it unique in the U.S. military.

Kirtland AFB in New Mexico

- Size: One of the largest Air Force bases, covering about 52,000 acres.

- ICBMs: Kirtland does not host operational ICBMs but plays a crucial role in research and development, testing, and training missions related to them.

- Role: Home to the Air Force Research Laboratory and other critical units; a hub for advanced research and development, including work on nuclear weapons and ICBMs.

The incidents documented by Project Northern Tier not only serve as an historical record but also as a pressing call for increased scrutiny on airspace security, particularly over areas containing potent nuclear capabilities. The role of ICBMs as a linchpin in national defense strategy makes any form of intrusion or interference a matter of grave concern. The advanced aerospace vehicles observed were not only unidentified but exhibited capabilities that challenged conventional understanding, directly compromising the operational integrity of these missile systems.

Given the global landscape where multiple nations possess ICBM technologies, the implications of these incidents extend beyond U.S. borders, raising questions about global security and the potential for unintended conflict. It underscores the urgent need for transparent international dialogues on aerial phenomena and advanced aerospace vehicles, as they have the potential to mislead defense systems and spark inadvertent crises. As nations continue to invest in the modernization of their respective ICBMs, they must also advance their understanding and protocols concerning unidentified aerial phenomena. To ignore these incidents would be to neglect a dimension of national and international security that we don’t fully understand, thereby leaving room for potentially catastrophic miscalculations.