Metaphysics

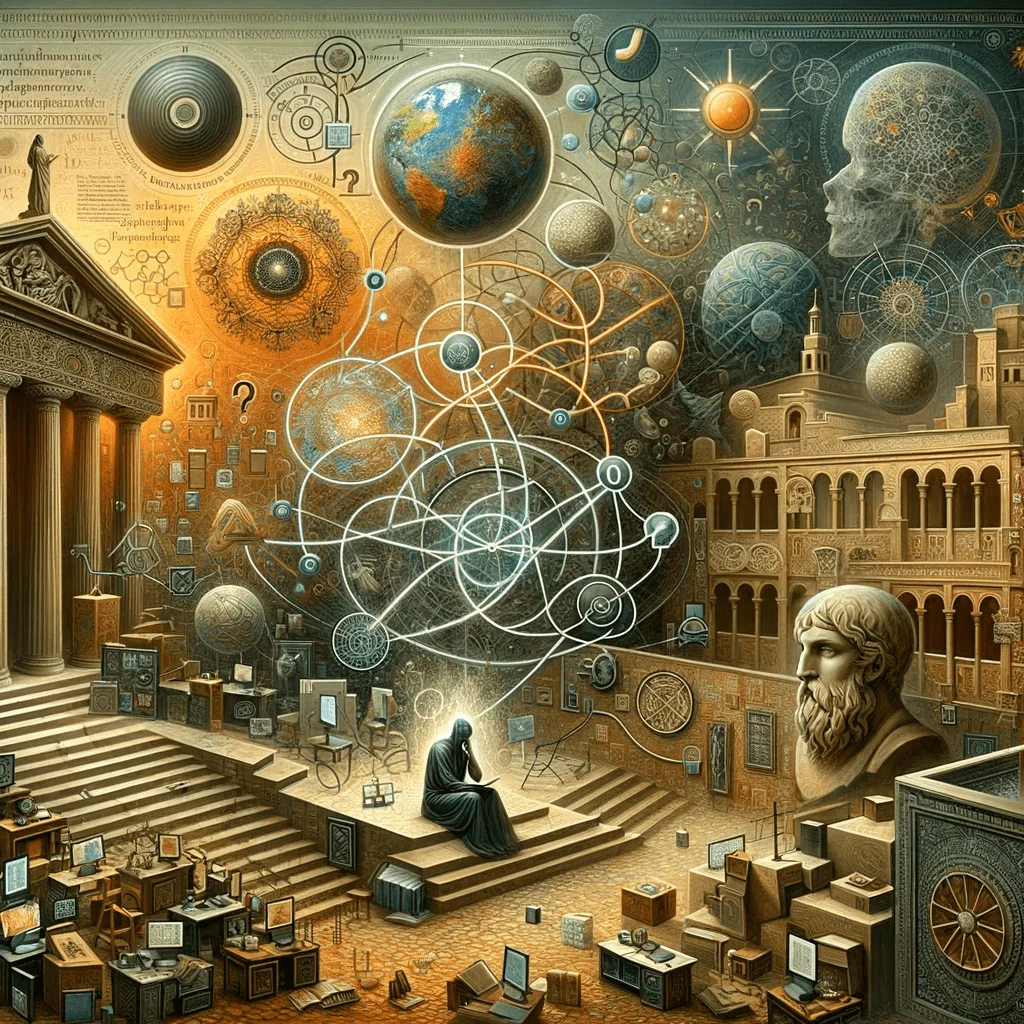

Metaphysics is a complex and profound branch of philosophy that attempts to understand and unravel the fundamental nature of reality. Historically, its study began with the ancient Greeks, specifically with the philosopher Aristotle. He first used the term “metaphysics” to refer to the study of “what comes after physics”, or, in a broader sense, to describe a study of “what is beyond the physical.” In Aristotle’s own works, metaphysics was primarily concerned with the principles of being and knowing, dealing with topics like existence, reality, consciousness, and causality.

Over the centuries, metaphysics has evolved, continually absorbing influences from various philosophical traditions and perspectives across the globe. From the quiet courtyards of classical Greek academies to the austere halls of medieval monasteries, the bustling universities of the Enlightenment era to the sprawling virtual classrooms of the 21st century, the quest to understand the nature of reality has been constant and unyielding. The “why” of metaphysics is rooted in humanity’s innate desire to make sense of the universe, to probe beyond the observable, and to grapple with questions that stretch beyond the limits of empirical science.

One key fact, verified by the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, is that metaphysics can be broadly categorized into two main streams: ontological and epistemological. Ontological metaphysics studies the nature of existence, looking into questions like what entities exist and how they might be grouped, related within a hierarchy, and subdivided according to similarities and differences. Epistemological metaphysics, on the other hand, probes into the nature and limitations of knowledge itself, questioning what is knowable, how we know, and what constitutes truth.

The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, notes that metaphysics also tackles the concept of “free will,” examining the intricacies of determinism, chance, and human freedom. This study of free will straddles the intersection between metaphysics, ethics, and psychology, revealing the broad interdisciplinary nature of this philosophical field.

Metaphysician, Graham Harman, author of “Object-Oriented Ontology: A New Theory of Everything,” asserts that everything has an essence that is both real and withdrawn, regardless of whether it is a physical entity, an abstract concept, or a human being. His philosophy is part of a newer movement called speculative realism, which pushes the boundaries of traditional metaphysics.

Books like “Being and Time” by Martin Heidegger and “Process and Reality” by Alfred North Whitehead continue to be fundamental resources in the study of metaphysics. Heidegger contends that the concept of “being” is central to metaphysics and that an examination of our own experience of being can shed light on metaphysical questions. Meanwhile, Whitehead proposes that reality is a process and that everything in the universe is interconnected.

The exploration of the nature of reality and existence has been a central pursuit of philosophical thought, tracing its roots back to antiquity and extending to our present-day scientific and philosophical discourses.

Ancient cultures often explained reality and existence through mythologies and cosmologies, attributing the creation and operation of the universe to divine beings or forces. These narratives, while not philosophical or scientific in a modern sense, nonetheless constituted an early attempt to grapple with existential questions.

Philosophical inquiry as we understand it began with the Pre-Socratic philosophers in ancient Greece. They proposed a variety of theories about the fundamental substance of reality, positing elements like water, air, or an indeterminate substance called the “apeiron” as the basis of all existence.

Plato, another ancient Greek philosopher, proposed a theory of Forms, suggesting that the ultimate reality consists of perfect, unchangeable ideas, and that the physical world is just a shadow or imitation of this higher reality. His student, Aristotle, introduced the concept of “substance” and “accidents,” arguing that individual entities exist in their own right (substance), but have properties (accidents) that can change without affecting the entity’s existence.

During the Middle Ages, philosophers, particularly those within the Scholastic tradition, sought to reconcile classical philosophical ideas with religious doctrines. St. Thomas Aquinas, for instance, introduced the concept of “existence as an act,” arguing that the existence of entities is not a static property but a dynamic act enabled by God.

With the rise of modern philosophy, thinkers like René Descartes posited a dualistic view of reality, differentiating between the material world (res extensa) and the world of the mind (res cogitans). In contrast, philosophers like Baruch Spinoza and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz proposed monistic views of reality, arguing that everything that exists is part of a single substance or is composed of simple, indivisible entities, respectively.

Immanuel Kant introduced a new perspective with his theory of transcendental idealism, arguing that our knowledge of reality is shaped by the cognitive faculties we use to perceive it. According to Kant, we can never know things as they are “in themselves,” only as they appear to us.

In the 20th century, philosophical investigations into the nature of reality and existence took a linguistic turn, with philosophers like Ludwig Wittgenstein suggesting that philosophical problems about reality often arise from misunderstandings about the use of language.

Simultaneously, the advent of relativity and quantum mechanics in physics revolutionized our understanding of reality. Physicist Albert Einstein showed that space and time are interconnected in a four-dimensional spacetime, while quantum mechanics introduced a probabilistic view of reality, with particles existing in multiple states simultaneously until observed.

Contemporary theories range from the multiverse theory in cosmology, suggesting the existence of multiple or even an infinite number of universes, to various interpretations of quantum mechanics, such as the many-worlds interpretation. At the same time, philosophers and cognitive scientists are exploring how our perceptions and cognitive processes shape our understanding of reality, a field of study known as cognitive ontology.

The question of the nature of reality and existence has been and continues to be addressed in various ways throughout history, shaped by the philosophical, scientific, and cultural contexts of different periods. It remains a fascinating and fundamental quest in our collective endeavor to understand the world and our place in it.