Napoleon Bonaparte’s Egyptian Expedition, Description de l’Égypte, the Rosetta Stone, and the Arch of the Simplon

At first glance, this might look like a historical deep dive into Napoleon Bonaparte’s Egyptian campaign. But hold that thought. This story runs deeper than conquest and archaeology—it touches the edges of something stranger, something echoing through time and space. Napoleon’s obsession with Egypt, the gods he encountered through his savants, and the symbols he embedded in stone may not have been just gestures of empire. They might have been signals—encoded links to something older and possibly interdimensional. What began as a military expedition may have doubled as a gateway to ancient knowledge that modern science still struggles to decode. Eventually, the connections will become clearer.

In 1798, Napoleon Bonaparte launched an ambitious military and scientific campaign in Egypt, a bold move that fused imperial conquest with Enlightenment-driven scholarship. His goal was not only to defeat the Mamluks and establish a French foothold in the region, but also to uncover, document, and study the ancient wonders of Egypt. To achieve this, Napoleon assembled a team of more than 160 scientists, artists, engineers, mathematicians, naturalists, and linguists—a group known collectively as the “savants.”

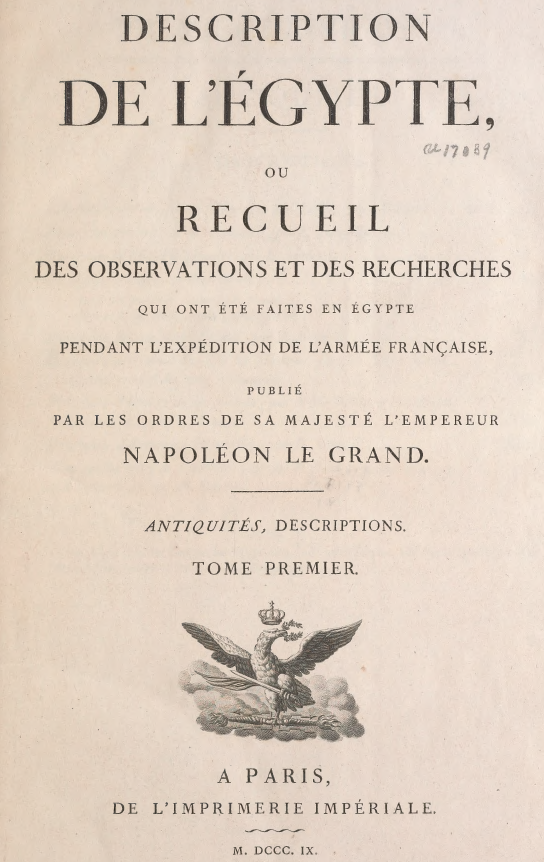

These savants were tasked with an unprecedented mission: to catalog every observable detail of Egyptian civilization, past and present. They measured temples, mapped cities, recorded hieroglyphs, studied the Nile, documented native flora and fauna, and explored the country’s vast archaeological heritage. Their findings were meticulously recorded in what would become one of the most comprehensive scholarly works of the 19th century: Description de l’Égypte.

This encyclopedic collection, published between 1809 and 1829, contains thousands of pages of detailed observations, illustrations, maps, and scientific notes. While its primary emphasis lies in scientific and cultural documentation, a notable portion is devoted to religious practices, temple architecture, and the symbolic role of gods in Egyptian life. The savants preserved visual and textual references to sacred imagery, reflecting a fascination with Egypt’s spiritual universe.

Among the deities explored in the book, Isis stands out, especially in the records from her temple at Philae. She is shown receiving offerings and presiding over rituals that portray her as a divine mother and healer. Her figure appears frequently in temple reliefs and ceremonial spaces, reinforcing her importance in both spiritual and royal domains.

Osiris appears as a central figure in the mythology of death and renewal. He is depicted as a mummified king holding the crook and flail, often seated in scenes of judgment. His presence in tomb art and temples devoted to the afterlife suggests the profound influence of his cult on funerary customs.

Horus, particularly emphasized in the temple at Edfu, is represented as a falcon-headed warrior god. The text elaborates on carvings that show his battle with Seth, a cosmic conflict symbolizing the victory of order over chaos. In other scenes, he is depicted as a divine child born of Isis, further strengthening dynastic themes tied to kingship.

Hathor appears in joyous and nurturing scenes, often portrayed with cow horns framing a solar disk. Found in places like Dendera, her depictions emphasize her ties to music, dance, and maternal care. The savants noted her wide-reaching presence and symbolic association with femininity and celebration.

Thoth receives less attention but is still identified in judgment scenes where he records the weighing of the heart. Depicted with an ibis head or as a baboon, he embodies intellect, timekeeping, and cosmic balance. His inclusion highlights the reverence for writing and order in Egyptian cosmology.

Khnum is shown as a ram-headed craftsman shaping human figures on a potter’s wheel. His imagery, especially from sites like Esna and Elephantine, was of great interest to the savants for its blend of mythology and symbolism surrounding creation and divine design.

Sobek appears in the reliefs of Kom Ombo as a crocodile-headed figure. His dual nature as both a protective and unpredictable force reflects the Nile’s own temperament. He shares temple space with Horus, symbolizing the union of instinctual strength and disciplined rule.

Anubis, with the head of a jackal, presides over rituals of embalming and transition to the afterlife. He appears near sarcophagi and in scenes of funerary rites, acting as a guardian of the dead. His imagery evokes reverence for the delicate journey between life and eternity.

Ra, or Re, the solar deity, is captured riding the sky in a celestial boat. With his flaming sun disk crown, he embodies the daily cycle of life, illumination, and divine authority. His imagery fills temple carvings and liturgical chants, underscoring the sacred rhythm of time.

Amun, merged in some contexts with Ra as Amun-Ra, dominates Karnak and Luxor. His tall crown and majestic figure appear in processions and ceremonial engravings. The savants documented rituals honoring him as the hidden force behind kingship and the god who energizes royal authority.

Napoleon is said to have spent a night alone inside the Great Pyramid of Giza. When he emerged, he appeared disturbed and refused to describe what had occurred, allegedly muttering, “You would not believe me if I told you.” The story endures that he encountered something inexplicable within the ancient chamber.

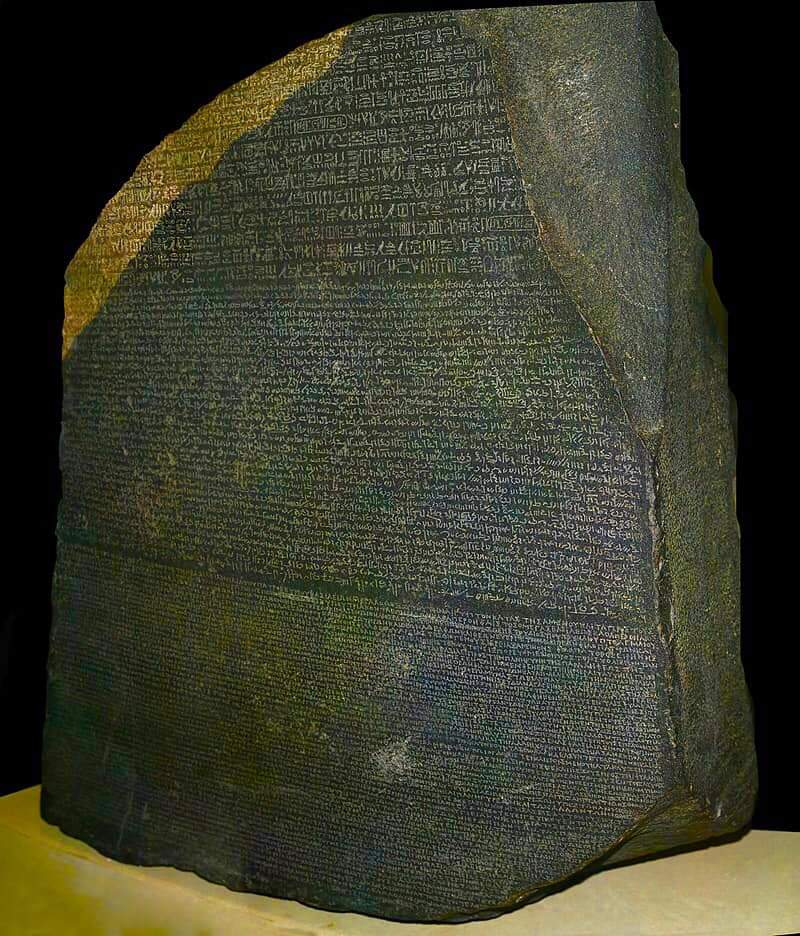

Napoleon surrounded himself with advisors attuned to esotericism. Several of his closest allies were Freemasons, and he understood the cultural power of symbolism and ritual. His use of Egyptian imagery and interest in mystical traditions reflect a belief that ancient civilization held secrets capable of bolstering his imperial image. One of the most significant discoveries during this expedition was the Rosetta Stone, unearthed in 1799 near the town of Rosetta by French soldiers. This granodiorite stele, inscribed with the same decree in three scripts—Greek, Demotic, and Egyptian hieroglyphs—enabled scholars to finally decipher the ancient writing system. The inscription itself is not mystical in nature; rather, it is a decree issued in 196 BCE under Ptolemy V, praising the young king’s generosity, religious piety, and support for temples. It commands that priests honor him and that this decree be engraved in all three scripts for maximum accessibility. Although the stone ultimately passed into British possession after the French defeat, its discovery was a direct result of Napoleon’s campaign. The Rosetta Stone became the key to unlocking Egypt’s linguistic secrets, and it later allowed Jean-François Champollion to decode hieroglyphs—revolutionizing the study of Egyptology and fulfilling one of the intellectual ambitions of the expedition.

Strategically, his goal was to interrupt British trade to India by taking control of Egypt. Yet it is clear that his fascination with the land extended well beyond tactical advantage. His exhortation before the Battle of the Pyramids—”From the summit of these pyramids, forty centuries look down upon you”—was meant to inspire awe and suggest continuity between France and ancient grandeur. His public message to the Egyptian people, “Peoples of Egypt, you will be told that I have come to destroy your religion. Do not believe it…” shows that he was keenly aware of the symbolic and spiritual importance of the land.

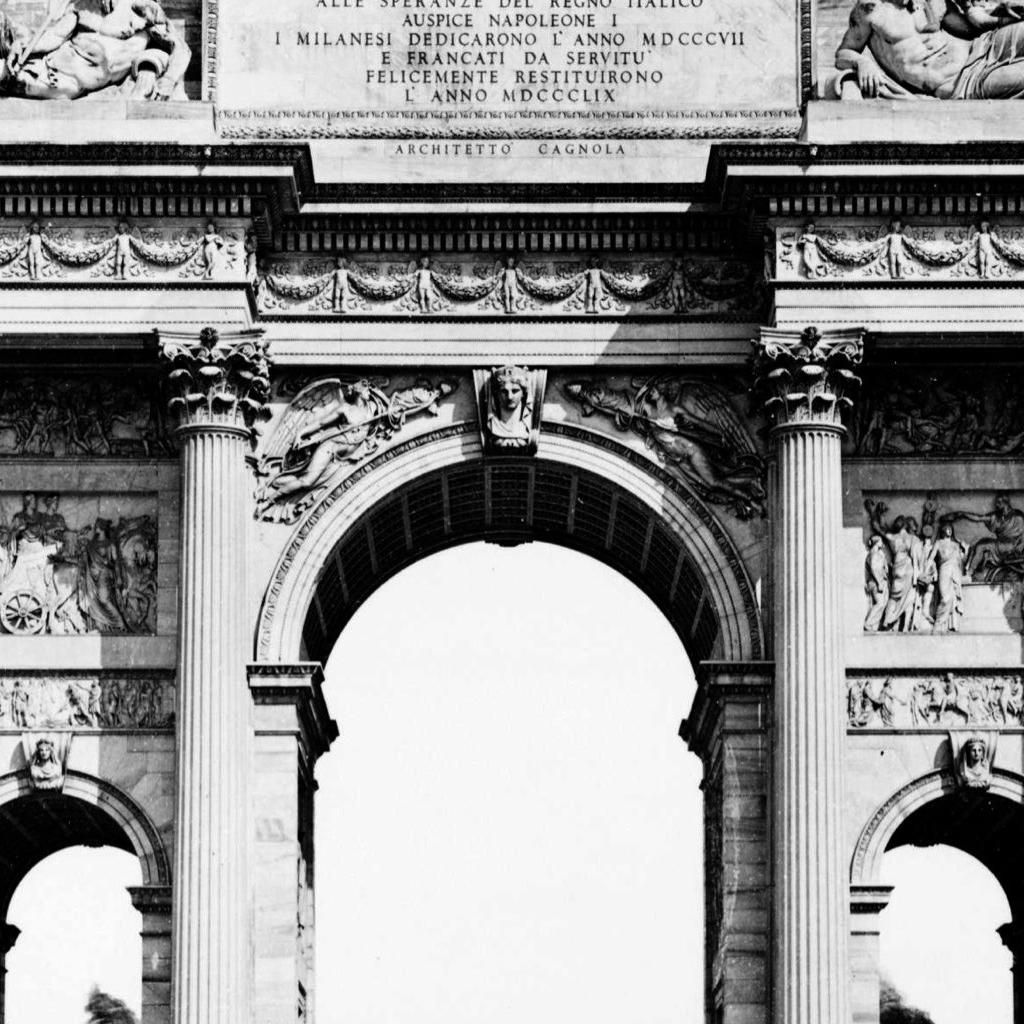

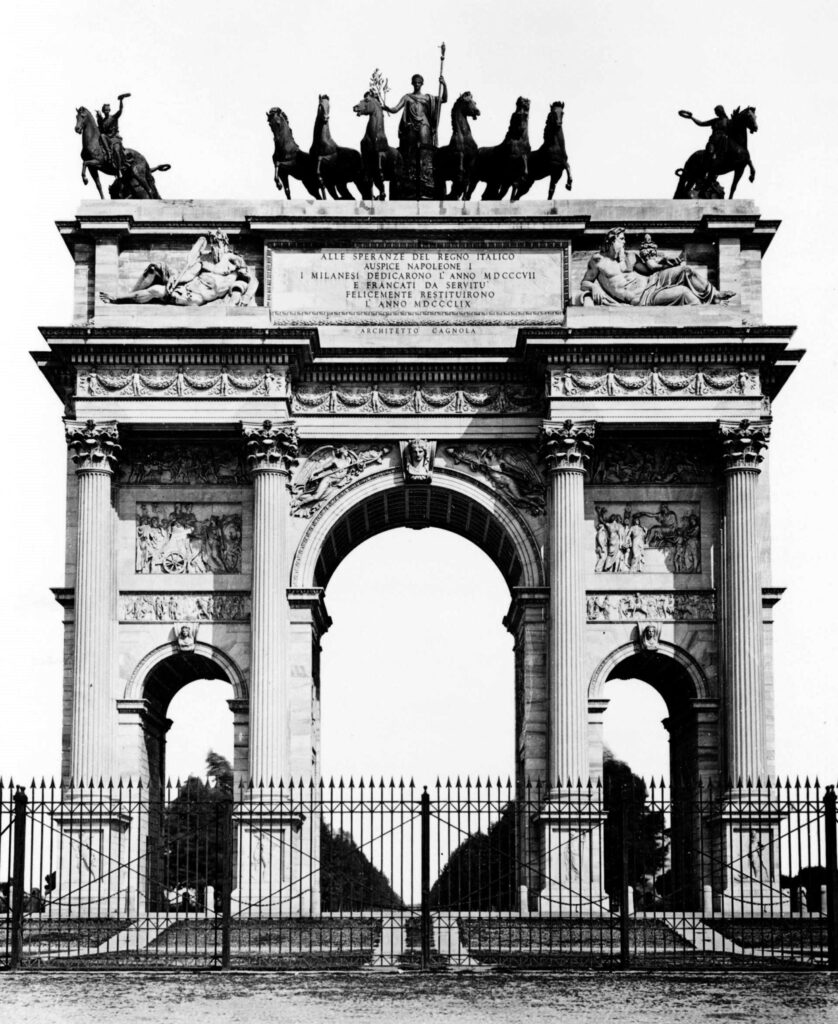

The Arch of the Simplon in Milan stands as a physical echo of these ambitions. Commissioned by Napoleon in 1807, it was intended to celebrate his victories and the engineering achievement of the Simplon Pass. The structure, designed by Luigi Cagnola, borrows from Roman triumphal arches but is steeped in neoclassical symbolism. Reliefs depict scenes of glory, mythology, and conquest. A quadriga crowns the arch, representing divine momentum and imperial success. After Napoleon’s defeat, the Austrians completed the structure and renamed it the Arco della Pace—Arch of Peace—reframing it as a symbol of calm after turmoil. But the original vision still lingers in its form and placement. The monument reflects Napoleon’s effort to link his empire to the splendor of ancient civilization. Like his Egyptian expedition, it channels Enlightenment ideals, esoteric inspiration, and the enduring pull of mythic legacy.

What starts with a military maneuver and ends in a triumphal arch carved with gods and cosmic power is no ordinary chapter in history. Beneath the official motives lies a quiet suggestion: that Napoleon, perhaps unknowingly—or perhaps not—brushed up against something older than civilization itself. The Rosetta Stone, now on display at the British Museum in London, gave us language. The temples gave us gods. And the Arch of the Simplon gave us a monument to something still unfolding. The pieces of the puzzle are scattered across timelines, dimensions, and belief systems. This is one of them. The meaning may not be fully visible yet—but it’s coming into view.